Presentation to Oregon Legislature Interim Judiciary

Committee

University of Oregon School of Law

Oral Presentation - September 29, 2000

What you see on the screen is what I look at every day when I start

up. This computer sits on my bench. I have been a trial judge for ten years

in Multnomah County and have handled all sorts of civil and criminal cases.

The image in the middle is a design for the prison, which was the invention

of Jeremy Bentham. Anyone with any exposure to the history of criminal

justice knows that prisons are relatively modern. They came from the same

time as when Lewis and Clark were coming through these parts with their

Newfoundland dog. If you back out of my website address, it will direct

you to my Newfoundland dog site. I have this

on my screen each morning to remind me that even though I am certain that

I have the answer to 90 percent of the problems you have been hearing about

this morning, so was Jeremy Bentham, and he was deadly wrong about a lot

of what he thought he was certain about. So this is a reminder of humility;

I think all judges need that routinely, and that is why it is on my bench.

In your materials you have something called "Paying

Attention to What Works;" it's a three page piece, a download from

the

website that I maintain in support of this process which I will soon

describe to you. It was an article in the Oregon State Bar Bulletin that

was published about a year ago, the August-September issue. The goldenrod

issue called Resolutions News is this

two page document that was just distributed. At the very bottom of the

front page you will see the website that I maintain all this stuff on,

and I will tell you what's there in a minute. Resolution News is

a newsletter, this is the fourth edition out today. I have been publishing

it primarily for Oregon judges to keep them apprized of developments in

this process. I give it to you because it describes -- it's a snapshot

of where we are in our progress now in the technological directions that

I'll describe in a minute, and also gives a handy cite to the web address

where you can look up everything else. If you remove the words "whatwrks.html"

from the website, you'll get into the Columbia River

Newfoundland Club web site, and it's fun too, but has absolutely nothing

to do with this.

First of all, I'd like to give one disclaimer, I have something of a

quirk, I don't want to call it a disability, a quirk, I can't remember

names at all. I have seen a lot of you before, and I will see a lot of

you again, and if I don't remember your names, it's probably because I

was dropped on my head in preschool. But one of the advantages it has given

to me is that when I listen to discussions about systems and their efficiencies,

I think I view them differently than most people. We all have to worry

about systems and how well they work, but when I start seeing prison modulation

based on changing the rules for revocation so they we can keep the bed

load right, it occurs to me that if we build a prison within a wide range

of possible capacities, we can make the system accommodate that capacity

just by focusing on the system's needs. I think that what we all do in

all of our worlds, including the judge world, is we focus on the needs

of the system instead of the purpose of the system. And with the deficit

of not being able to stay on that groove, I can't carry a tune, I cannot

continue to look at systems only for their own interests. Every once in

a while, I lose track and I realize that there is a purpose. Along those

lines, let me give you first this -- it is the same statistics as on that

downloaded piece of materials here. This is one way of looking at the problem

of recidivism, and as someone mentioned this morning, recidivism can be

measured in all sorts of ways, and for reasons that I will explain later,

I think it is critical to remain able to redefine what you mean by recidivism

within a fairly narrow range, that has to do with criminal behavior, but

for different people for different occasions, you may want to look at different

measures of recidivism. I will give you an example of that.

Portland Police Statistics for Jailed Suspects

For Persons Arrested During July 2000

|

Charges

|

Number jailed this month

|

Of those jailed this month,

the number also jailed

within the last year in Portland

|

|

All

|

2395

|

1246

|

|

Burglary

|

32

|

22

|

|

Robbery

|

23

|

22

|

|

Felony Assault

|

33

|

22

|

|

Theft I

|

26

|

20

|

|

Felony Drug

|

372

|

304

|

|

Theft II

|

61

|

36

|

|

Misdemeanor Assault

|

160

|

68

|

|

Menacing

|

70

|

47

|

|

Trespass

|

80

|

53

|

|

Motor Vehicle Theft

|

39

|

32

|

Source: Portland Police

Bureau Data Processing, August 25, 2000

This is one way of looking at recidivism. These are statistics published

by the Portland Police Bureau every month, the most recently published

statistics are from August, 2000, they are a little behind, that is August

publication date, July is the month. The way to read these statistics,

which I have extracted from a bigger chart which gives you more information,

is the first row is the number of people jailed in Portland for anything

in July of 2000. The next column is the number of those who are in jail

for something in Portland within the prior 12 months. So if you look at

burglars, of the 32 burglars in jail for burglary, not necessarily burglars,

in jail for burglary, 22 of them had been in jail in Portland for something

else within the 12 months. Of the 23 jailed for robbery, 22 had been in

jail in Portland within the 12 months previous for something else. I have

just confirmed that these do not include the original charge, that is to

say you are not counting the first arrest on a robbery and they are arrested

again. And if you look through those -- look at the drugs, 372 people jailed

in July, 304 of them had been in jails in for something in Portland before

that, and so on. There are indeed some first offenders who are very numerous

in the system that don't come back. They tend to be first time DUII offenders;

they tend to be first time male prostitution defendants. The rest of them

-- and this is what occurred to me very soon after being on the bench,

was that the first offender you see in the courtroom is a very rare critter

indeed. When I hear an attorney say "this is my client's first offense"

I immediately say "Please don't put it that way" say "it's my client's

only offense," because most of the people we see are in the middle of criminal

careers, and until we start looking at their careers as careers, we won't

start addressing the problem. And until we do a better job of deciding

what it is we are to do to these people when we have the option of doing

it to them -- and as judges and in the correctional system our hit

is as they come into the courtroom and get convicted -- other people have

other hits -- people have release decisions to make; people have supervision

decisions to make, people have decisions -- in 1996 NIJ and the Citizen's

Crime Commission put out a joint session very much like this just before

the legislative session. What we heard was, if you want the most return

for your dollar of investment: high school completion, parenting education.

If you want the best return for your money, do it there. But as a judge

and a participate in the criminal justice system, my best shot at these

people is when they come into my courtroom and their convicted, and I have

some discretion. What these figures indicate is that we are doing a terrible

job, a terrible, terrible job. They mean for example that the robberies

that occurred, some of those robberies are victimizations that we could

have prevented had we been smarted, but we didn't even try! We didn't even

try because when we do sentencing decisions, we never ask the question,

"how is your recommended sentence most likely to prevent the next victimization."

When I ask that of lawyers their jaws drop, and people who are perfectly

capable of holding forth on mitigation and aggravation as if those things

were quantifiable are speechless when I ask that question. And they're

speechless only because they don't get asked that question. I think the

most important thing we can do in criminal justice is routinely and rigorously,

and conscientiously to ask that question.

Why is it that we are like this?

But when it comes to sentencing, they look a lot like the guy who was

around in the period of the Black Plague.

|

And I suggest to you that one of the interesting wrinkles about the

argument for judicial discretion is that most of us think we know very

well what works and what doesn't work. But you know, we don't test

it, and we don't rely on knowledge. And frankly, my opinion is that we're

no better at what we do without access to good information than this fellow

was in his day in the Black Plague. |

|

We have started to work on that problem. In 1997, we passed a law, this

was 1997 House Bill 2229. . . . I'll take you through

it quickly. The full text is on the website if you want to examine it.

It did several things. Its purpose was first of all to articulate as had

rarely been done before that public safety is really one of the things

that you should measure criminal justice's performance by. Believe it or

not, it took a constitutional amendment in 1996 to put that into our constitution.

And it took this bill to put it in all the places you will see it in --

that public safety should be the measure, recidivism reduction should be

the measure. This [bill] did a lot of things. One thing, it linked juvenile

and adult data so that we can see the impact of the choice we make on juveniles

as to their criminal careers as adults. We had an Oregon Criminal Justice

Commission. It does a lot of the things that the Texas commission [subject

of another speaker's talk at this session]. We added to its planning function

the duty of providing "methods of assessing the effectiveness of juvenile

and adult correctional programs, devices and sanctions in reducing future

criminal conduct." That as an outcome measure hadn't been adequately articulated

and certainly hadn't been adequately practiced in our system. The Department

of State Police shall establish "the Criminal Justice Information System,"

CJIS, the "system" now being "standards," we changed that at their request,

but CJIS is supposed to be doing something new as a result of HB 2229,

and that is "[E]nsure that in developing new information systems" --

that's information technology -- "data can be retrieved to support evaluation

of criminal justice planning and programs, including . . . the ability

of the programs to reduce future criminal conduct." A simple concept, but

it needed to be stated. The Youth Authority "reformation plan" was fiddled

with in this fashion: to require that the plan be aimed at "reduc[ing]

future criminal and antisocial conduct"; that the Youth Authority should

cooperate and "to the extent of available information systems resources,

shall share data with the Department of Corrections" to see what happens

to adults after they've been dealt with in the juvenile system.

The Department of Corrections, which already had an information obligation

have that obligation modified to make sure not only that it could track

offenders, but that it would "[p]ermit analysis of correlations between

sanctions, supervision, services and programs, and future criminal conduct."

Again, a modest proposal in any other world, but it hadn't been articulated

here.

I'll take you through the rest quickly and describe it to you generically.

What you see next is that the Youth Authority and the Department of Corrections,

under the various bills that return a lot of responsibilities to local

jurisdictions in partnership with private providers and community-based

providers, part of the deal has to be shared information so that we can

do this kind of assessment.

In the same year, 1997, the Judicial Conference, of which I'm a member,

and I now chair the Criminal Law Committee of the Conference, this

is a resolution that was introduced first in the '96 Conference, we

set up a committee, which is, after all, traditional to deal with things

that might be controversial, the committee met and produced this resolution

which was passed. It reviews the provisions of Oregon law about what the

purposes of sentencing are. The second paragraph is the Article I, section

15 amendment which says that "[l]aws for the punishment of crime shall

be founded on these principles: protection of society . . . ." which entered

the constitution as a purpose of criminal justice, of sentencing, in 1996.

The rest of the statutes are there for your review, but the "therefore

clause" is: "THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE OREGON JUDICIAL CONFERENCE

that in the course of considering the public safety component" -- there

are other components of sentencing -- judges are to "invite advocates to

address" and themselves to consider "the likely impact of the choices available

to the judge in reducing future criminal conduct."

That's precisely the question that jaws still drop when you ask it in

the courtroom. Defense attorneys and prosecutors are rarely prepared to

enter the courtroom and answer or address that question.

The last resolution here says that "judges are encouraged to . . . obtain

training, education and information to assist them" in making these choices.

So the policy declarations have been made. Publicly, we have learned

that one of the issues we are to address in making sentencing choices --

and we have many choices left; in 90 % of the case in which I impose sentences

I have tremendous discretion. Ballot Measure 11 is of course important

for big cases, but the great bulk of cases coming through the courthouse

are not Ballot Measure 11 cases, and there're questions about whether to

use jail or not, how much jail to use, whether concurrent or consecutive

sentences ought to be used, what conditions to report, whether to revoke,

when to revoke, what additional conditions of probation to impose if you

don't revoke -- there's tremendous discretion in the courtroom every day.

What we have been doing in Multnomah County, and what we hope will be the

precursor of the Public Safety Data Warehouse, which the State Police Department

is constructing, is to produce a tool which is to be used by judges, advocates

for and against the State, for and against the defendant, probation officers

in supervision, release officers, correctional officers for people in custody

-- to match offenders with the response that works for similar offenders,

with "works" being defined by reduced crime.

The technology that this uses is a technology that is employed regularly

in every industry that has to compete for its survival. It's a little late

in coming to the Judicial Department, a little late in coming to government,

because the judiciary profits from its failures. The more of our cases

that come back as recidivists, the more demand there is for judges, prosecutors,

police, prisons, the whole industry. I'm not suggesting -- I'm not a conspiracy

theorist -- I don't think people are consciously planning to increase their

profit by undermining rational justice. I think the problem with justice

is that it still has some very medieval roots. And although those roots

have some proper role, they have no business displacing entirely a rational

approach.

This technology is data warehouse technology. It is just the current

state of the art for how you approach such a problem. Its critical factors

from a technological point of view, and the ones that are important for

this discussion, are first, that it draws on operational data. This is

not supplied by people sitting down for the purpose of collecting information

to support this analysis. This is a process that pools data from multiple

sources within the criminal justice system, for the purpose of preparing

and comparing analyses which help us all make better decisions.

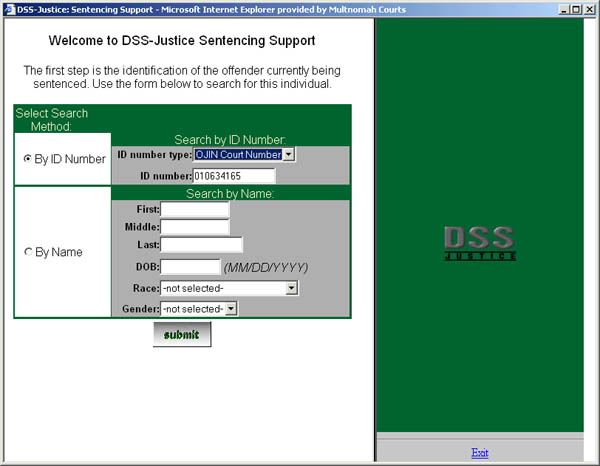

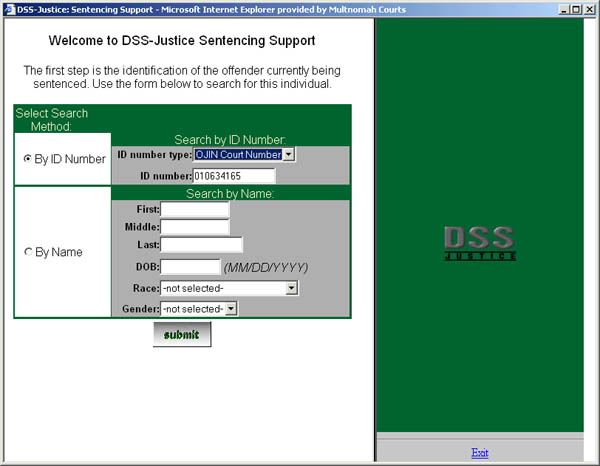

Now

I'm not connected to the database. What I'm about to show you is just a

demonstration of how it works. It's not actually working, although the

screens that you will see are actual screens from actual queries against

real data. The piece that I'm proposing and promoting, and the one that's

growing I think state- wide, very slowly, but growing, is the Sentencing

Support Tool. The way it works for judges is that typically you would enter

an OJIN number -- you can select any of a great number of identifiers --

you can use a name and search if you don't have a number -- and the case

number. The way our court system works is that the [OJIN]

Now

I'm not connected to the database. What I'm about to show you is just a

demonstration of how it works. It's not actually working, although the

screens that you will see are actual screens from actual queries against

real data. The piece that I'm proposing and promoting, and the one that's

growing I think state- wide, very slowly, but growing, is the Sentencing

Support Tool. The way it works for judges is that typically you would enter

an OJIN number -- you can select any of a great number of identifiers --

you can use a name and search if you don't have a number -- and the case

number. The way our court system works is that the [OJIN]

case number identifies an individual.

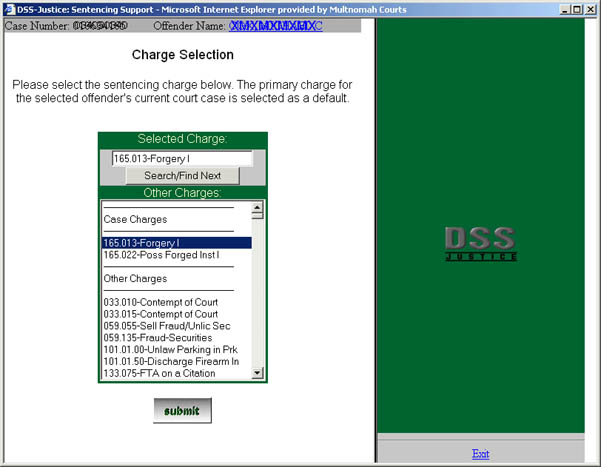

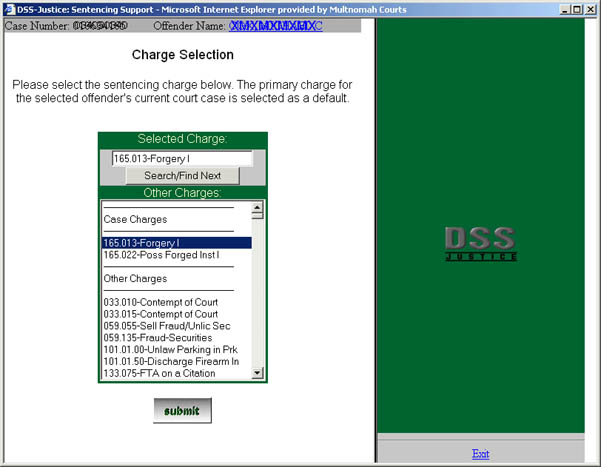

When you "submit" that information, you then get a screen which allows

you to select the charge for which you are sentencing this individual.

It proposes count one. It gives you the other charges in the case, and

then allows you to search for and to select any criminal charge known to

Oregon state or local law. So if you have an ordinance against littering

in Eugene, it'll be here, because when you actually get to sentencing,

you may be sentencing on a charge that's very different than the one that

was filed. When you submit that, the program goes to work. What it's doing

now is accessing data that's already been collected from operational systems

for people who it knows to be like the offender. You've identified the

charge, Theft in the Second Degree. It knows who the defendant is and can

extract his criminal history is from the various data bases, and it can

compare him with all of the people who are like him who have been sentenced

for a property crime, and give you the results in terms of new criminal

activity for all of the elements of [sentences available] for that crime.

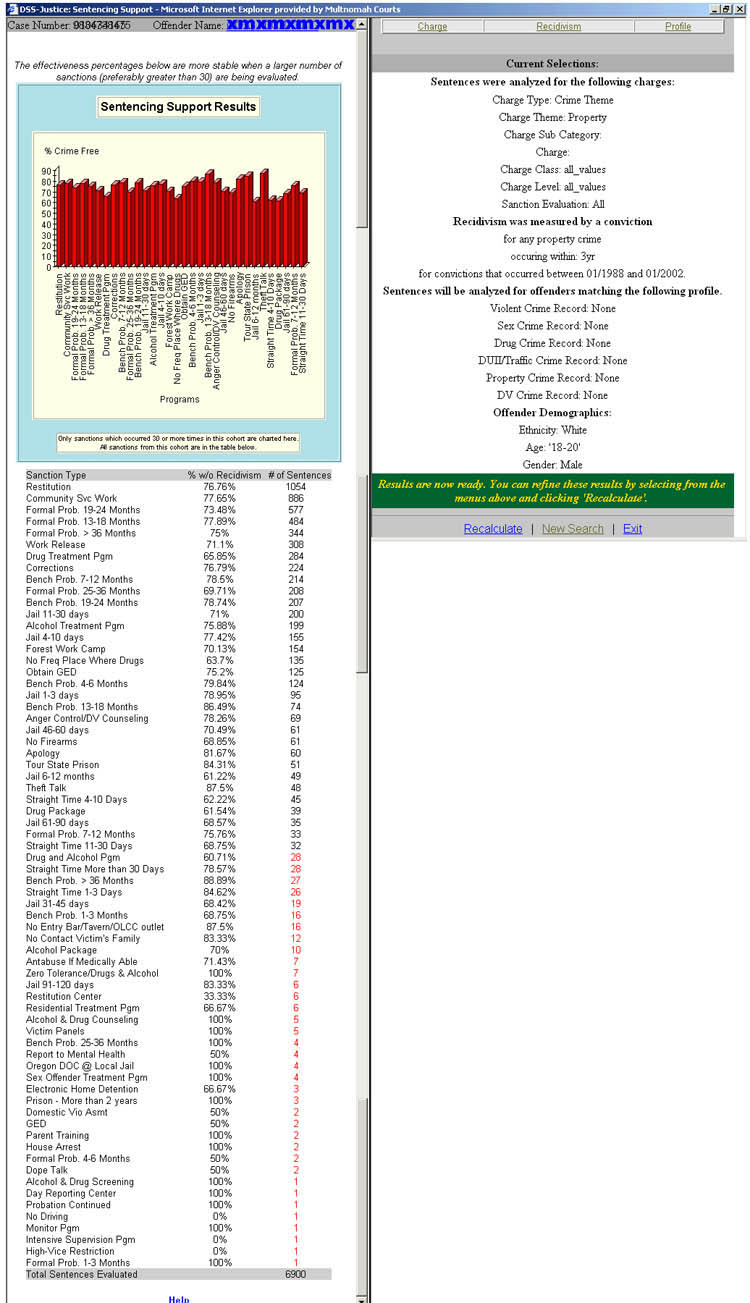

When you finally get the results, which typically takes about 90 seconds,

what you get is a bar chart.

Let

me concede at the outset that we are at the very threshold of using this

technology. When this finally worked against real data, I sent an e-mail

to judges on an international mailing list comparing this to Kitty

Hawk. We have as far to go [as the Wright Brothers did to get to] a 737,

but it is as profound a potential change as that flight at Kitty Hawk was.

Let

me concede at the outset that we are at the very threshold of using this

technology. When this finally worked against real data, I sent an e-mail

to judges on an international mailing list comparing this to Kitty

Hawk. We have as far to go [as the Wright Brothers did to get to] a 737,

but it is as profound a potential change as that flight at Kitty Hawk was.

This has not been done, as far as I can tell, anywhere else in the world.

But it's happening in Oregon, and I think it's spreading. I hope you will

see some of the reasons it's spreading.

In this bar graph, from left to right, in order of frequency, we get

bars representing sentencing elements: Restitution, community service work,

probation 1-18 months, jail 11-30 days, jail 4-10 days, forest work camp,

and so on. Below the bar chart is a table that lists all of the raw numbers.

When you get into the red numbers, they are below 30, and they are not

showing up as bars. That's roughly equivalent to statistical significance

to the extent that that's of concern. We don't display bars for things

that are too rarely imposed. Lurking under each of these three tabs are

the assumptions that the program made about this sentencing occasion.

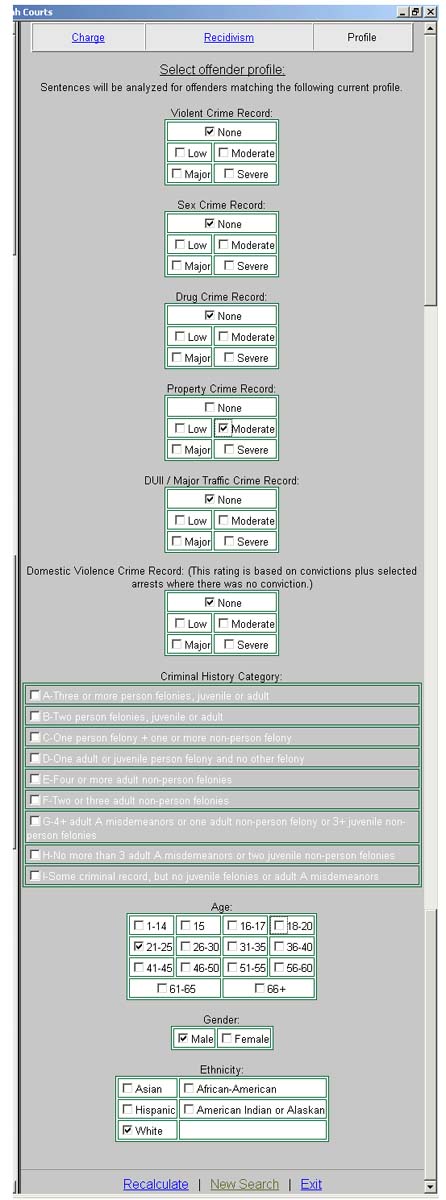

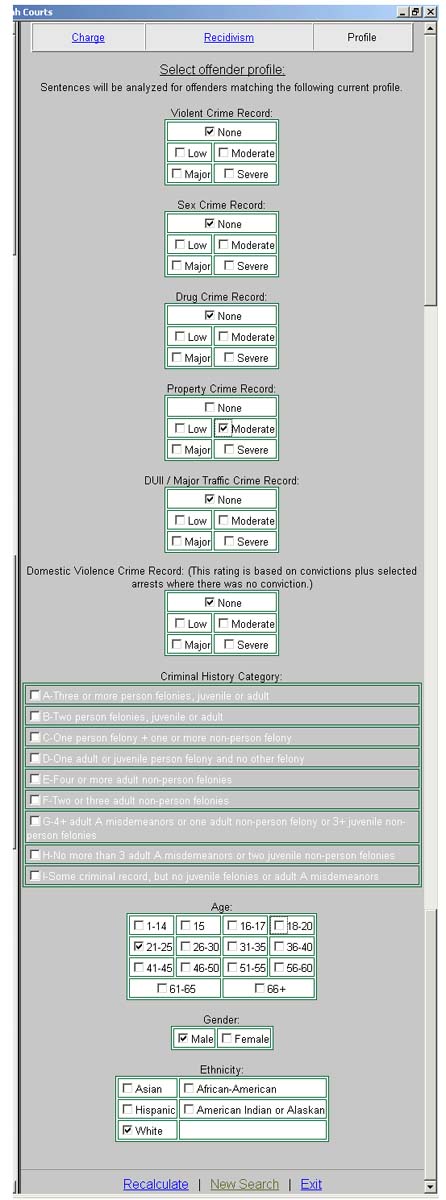

For

example, you will recall that we are sentencing this defendant for a Theft

II. So the program defaults to comparing only those people sentenced for

property crimes. You can change that [under the "Charge" tab]. What

we know about this defendant is lurking under the "Profile" tab. And what

we've done, and I think this is an innovation which is itself pretty important

-- criminal histories vary, and it's not just whether they're felonies

or misdemeanors, or how [frequent] they are, but they vary according to

themes. Some people are property criminals with drug involvement, some

have drug involvement with sex crime involvement, some are violent, some

are not, and so forth. We've established data rules for each of six categories,

ranking people from "none" to "severe" in crimes of violence, sex crimes,

drug crimes, property crimes, DUII/major traffic, and domestic violence

crimes. These crime themes boxes are calculated based on what the databases

contributing to the warehouse know about this offender. the Criminal History

score, here, is gathered from the last occasion on which the person received

a sentencing guideline under the regular "criminal history" [as designated

under the sentencing guideline rules]. This offender is 18, or that's what

we understood coming into this [this graphic shows other age boxes checked

by a user; it began with only the 18-20 box checked], and we know his ethnicity.

For

example, you will recall that we are sentencing this defendant for a Theft

II. So the program defaults to comparing only those people sentenced for

property crimes. You can change that [under the "Charge" tab]. What

we know about this defendant is lurking under the "Profile" tab. And what

we've done, and I think this is an innovation which is itself pretty important

-- criminal histories vary, and it's not just whether they're felonies

or misdemeanors, or how [frequent] they are, but they vary according to

themes. Some people are property criminals with drug involvement, some

have drug involvement with sex crime involvement, some are violent, some

are not, and so forth. We've established data rules for each of six categories,

ranking people from "none" to "severe" in crimes of violence, sex crimes,

drug crimes, property crimes, DUII/major traffic, and domestic violence

crimes. These crime themes boxes are calculated based on what the databases

contributing to the warehouse know about this offender. the Criminal History

score, here, is gathered from the last occasion on which the person received

a sentencing guideline under the regular "criminal history" [as designated

under the sentencing guideline rules]. This offender is 18, or that's what

we understood coming into this [this graphic shows other age boxes checked

by a user; it began with only the 18-20 box checked], and we know his ethnicity.

Now I understand, and this keeps coming up for good reason, that ethnicity

is an issue. One of the things that I need to tell you , of course, is

that is that you can change any of this and you can take ethnicity out

simply by unclicking.

You can say well, I don't like my client being treated because of his

American Indian or Native American ancestry as a Native American, you can

unclick that, you can treat it as if he were like anybody else. You can

click all the boxes or none and recalculate. The reason we have ethnicity

in there is because there are programs in most communities, certainly in

Multnomah County, that target ethnic groups, minority groups for special

programs like House of Umoja for African American youths, there's NARA

-- Native American Rehabilitation Association -- for Native Americans.

What we want to be able is to carry the treat programs that aim there approach

to specific groups, so in order to compare outcomes we need that flexibility.

In addition, the ability to slice the offender population by ethnicity

may be necessary to account for disparities caused by racial profiling.

In other words, if a member of a given minority is more likely regardless

of criminality to be arrested, prosecuted, and convicted of crimes, it

is neither fair nor accurate to compare that person with non-minority offenders

whose criminal records although apparently equivalent actually represent

a higher level of criminality.

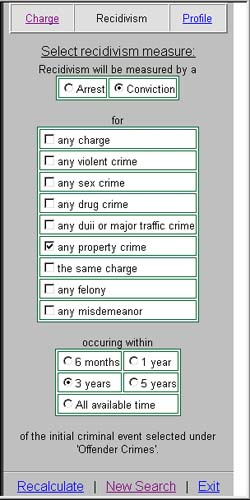

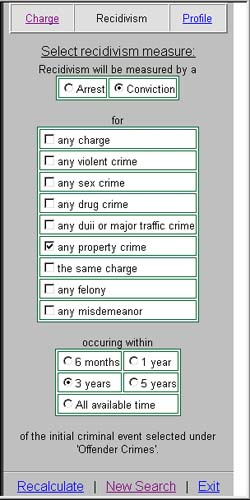

Let me go to what

I think is at least responsive to the question of uniform recidivism measures.

Because this offender is a property offender, the program decided to start

with a measuring recidivism by a conviction for a property crime within

three years of the sentence that it is comparing. And this little window

right here selects the slice of data that you are looking at -- by default

it is 1988 and 2000.

Let me go to what

I think is at least responsive to the question of uniform recidivism measures.

Because this offender is a property offender, the program decided to start

with a measuring recidivism by a conviction for a property crime within

three years of the sentence that it is comparing. And this little window

right here selects the slice of data that you are looking at -- by default

it is 1988 and 2000.

What is critical about this is, if I were sentencing a property criminal,

as I have, for a property crime somebody whose real problem is violence,

and I just happen to have the property crime, I might very well want to

look at violent recidivism by people so sentenced. You need to be able

to look at various recidivism measures. You can talk about what it is you

can

accomplish. If there is an opportunity to accomplish something significant

for an offender, something that may not be precisely involved with the

crime of conviction, but you can reduce his violence or his likelihood

of reoffending as a sex offender, but you have him on a drug charge, you

need to be able to look for that. It is an opportunity; you need to be

able to see it and argue about it. But let's say instead of worrying about

property crime only by Shawn Hermo, we want to change it to any charge

occurring within five years -- so we've just changed the outcome measure.

In the courtroom or in preparation for the hearing, or by probation officers,

you can hit recalculate, and we get a new set of bars because we have just

changed the outcome measure. Now we're looking for the same group of people,

sentenced for property crime, based on the likelihood that they are going

to succeed by the recidivism measure, which we have changed: any crime

within five years.

We can also change the profile. Let's say that we found out now that

we get to see this offender, he's not really 18 to 21 at all. He is really

old. He's really 26, so we click 26 and we recalculate and we get completely

different results.

Now one of the reasons we might want to recalculate is we may have learned

more in the courtroom about criminal history. We may have learned that

something attributed to this offender that doesn't belong him. We may have

learned how that something came from Arkansas puts him in a different category

altogether. We can make the change and rerun the calculations.

But we have a long way to go. This does not by any means represent the

complete pinnacle of this opportunity to aim sentencing decisions at more

effective results. I give you two propositions. One is we are doing a horrible

job of preventing reoffense. That's gotta be obvious to anybody who takes

an objective look at the statistics, and I showed you the ones involving

the problem -- 22 of the 23 arrested for burglary were in jail for something

else. That's one pretty good danger signal that we are not making the best

choice. But why are we not making the best choice? Because we are not even

trying without this kind of approach. It's not the discussion we have in

the courtroom; it's not the discussion either in probation revocation.

What works has to be part of the discussion in the courtroom and this tool

will make that part of the discussion in the courtroom, just as the sentencing

guidelines make the guidelines the discussion. When somebody walks into

the courtroom at a felony sentencing, they carry the grid. So when judges

and attorneys are used to looking at this, it will insist by its presence

that at least part of the discussion be about what is most likely to reduce

criminal behavior. We have a long way to go. We have to look at the composites

of sentences, the program ought to be smarter, as I described in that goldenrod

piece that I passed out, called Resolution News. And by the way,

the

resolution I read to you from the Judicial Conference -- the "therefore"

clauses are part of a masthead. "Resolution News" is that resolution,

and this is a device by which I keep judges apprized of our progress. The

progress is very frustrating in it's speed; it is steady, but it is slow,

and it's slow for all sorts of reasons. The one which is obvious to me

is that government organization information technology is a very different

animal than information technology in the private realm. Multnomah County

has made its great surge forward because we got a bond to support criminal

justice uses and we hired some consultants who are essentially from private

industry. The fellow who started this data warehouse project came to us

from American Express.

If you go to a hospital today, chances are your treatment is presumed,

based on an analysis of how people similarly presenting fared after being

treated with a range of things that could happen. Why? Because HMOs have

a profit line, and if they don't do something to you that is cost effective

by reducing the likelihood that you're going to come back with a more expensive

diagnosis next time, they are wasting their money and somebody else who

will compete them into the ground. We need to apply the same smarts to

criminal justice. This is not the only purpose of sentencing, but it is

critical to gain any respect in the community, and I frankly think that

the way to get any respect is to start focusing -- holding judges accountable

-- which is the way our new Police Chief in Portland put it -- holding

the courts accountable for their product.

As long as we can walk around in the modern equivalent to that

===}>

and say that our job is not public safety, our job is just deserts,

our job is "sending a message," our job is making the "punishment fit the

crime." |

|

If you want to send a message do it there ==}>

Let us know if you get a response. |

Giant Antenna at Arecibo used for SETI

Giant Antenna at Arecibo used for SETI

(search for extraterrestrial intelligence)

|

If you want to do something about public safety, if you want to

do something about criminal justice, then do what we can to make better

choices about whatever percentage it is of our criminal population that

we can actually divert from criminal careers.

Now, I have no idea how many people we can actually divert from criminal

careers, but I do know that our problem is criminal careers, it is not

one-time crimes. Sure, there are some one-time crimes that we need to deal

with, but most of the people we see keep coming back, they keep coming

back in tremendous number, and I cannot believe for a second that we are

doing as well by accident as we could do if we made a conscientious effort

to use good tools and good data to make better choices with the outcome

as a piece of the goal. I would be happy to answer questions.

A: How many of your fellow judges are capable of using this system?

Q: The system -- we have trained five data users, and have them hooked

up; they have access to the device and they can use it. We have trained

a small group of defense attorneys as beta users and Tom Cleary is arranging

a meeting and training for district attorneys. It's not part of the process

in any other courtroom yet, but speed is not our most important product,

in spite of the numbers you may have seen; not many is the answer.

Q: I was going to ask Judge Ross if this is a tool that could be used

in North Carolina because in all the conferences I have attended, yours

is the first presentation I've seen like this.

A: There's interest in the idea, Tom Simpson who is one of the two managers

of the project is from from the Multnomah County DA's office. He's been

going around to counties, a lot of counties are very interested in this,

and in trying to emulate it, we have been getting a lot of interest from

the Center of State Court's is interested in this, and we've been getting

inquiries from Nigeria, Scotland, Australia and Canada, but no one else

is doing it. By contrast, you saw the (image of) the judge with the computer,

there is a sentencing support system in New South Wales, and there is another

one in Scotland, and what it does, the one in New South Wales, does this.

It gathers a lot of information about the treatment programs, and a lot

of information about the offenders, and then it gives you a chart that

shows you what judges usually do. And the assumption is that you should

do what judges usually do. Why? Because judges know so much. Well if judges

know so much about what to do, how come the recidivism rates are so high?

I say do not try to emulate what judges do.

Scotland's gone a step further and they have built models which try

to emulate judicial thinking. Anybody who has tried to work with more than

one judge at a time, that's a very scary thought, emulating judicial thinking.

Judges are conscientious, many of us are actually pretty smart, and most

of us want to do the right thing. But all of us have no access to this

kind of information and therefore we rely on folklore, mythology, whim,

ideology, philosophy, personality to come up with what we think is right.

And if we pronounce it with the right tone of voice, people think well,

that must work, and that's what happened with the guy with the beak. Everybody

thought he was a doctor, so he must be right. Well, judges aren't right

unless they have the right information.

Q: My name is Bridget Jones and I am with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation,

Juvenile Justice Initiative. There are a couple of things that I would

like to ask you about. I find this prospect kind of scary. First of all,

it doesn't take into account or does it take into account things like the

subjective nature of charging; does it take into account the facts of the

case. Stealing something to eat is different than stealing something for

pleasure, and the other thing is where does mitigation and aggravation

come into this equation.

A: First of all, this is not a sentencing program. It does not give

you a sentence after you input data. It's a piece of information that you

have

in addition to the other information that comes to you in the sentencing

process. And of course the nature of the crime, is it typical of the crime,

the aggravation, mitigation, was it an excessive or an insufficient sentence

. . . You may find for example that somebody who has killed somebody with

a car who, because of their background, is completely safe on probation,

and yet for reasons other than public safety you would still use incarceration

because there are other components (of sentencing). Likewise, you are not

going to put somebody in jail who shouldn't be in jail because that's excessive

under the circumstances, because of somebody who steals literally to eat,

when they have exhausted the other choices. It is not supposed to make

decisions for judges, it's supposed to focus the process on something other

than whim, ideology, mythology and the secular version of religion, to

determine public safety, because it hasn't worked.

Q: My question though is you are using it as a factor to determine whether

that person is going to reoffend or not, is that correct?

A: What the program gives you is how some people who are similar in

at least in those aspects that you can retrieve from the database have

performed after you have done the things that you might do to this person,

so yes, to that extent you are using that information.

Q: And that's based on raw data, the charge itself, what was done as

a result of that charge. Is there any place in this program though that

speaks to some of the factors that are behind that data?

A: The program is limited to the data that's available, and there are

limits on the data that's available, absolutely. The problem -- I certainly

understand, æcause I've seen it -- that the idea that people will

somehow become insensitive to the details of the individuals or will be

insensitive to the policies of the local prosecutor, or the plea bargain

process or whatever it is, in coming up with a sentence which is driven,

which is not representative of the crime initially charged, and this program

doesn't address that. But what it does do is that it competes with unbridled

discretion where it exists for public safety. And frankly, if you look

at the data that you get back, I think most people who are concerned with

excessive punishment for minor criminals will find that indeed the lighter

sentences work better for lighter criminals, so look at the results before

you are too afraid of them. What I am afraid of, is a criminal justice

system which so profoundly fails to serve public safety, with the result

that the public's understandable reaction is simply to lock more people

up longer and longer without using prison to focus on the people who really

need to be there. And much more importing is diverting from criminal careers

those budding criminal careers which can be diverted before they become

fodder for extreme victimization and for the extreme result of the Texas

prison system.

Q: Thank you.

Q: I'm Ross Shepherd, the Lane County Public Defender. Has your program

been helpful to you in drug cases, in determining what sort of treatment

or alternative sanctions are appropriate in individual cases?

A: The program has not yet really been used in drug cases, it's actually

rarely been used at all. In my view it has tremendous potential because

we (now) lump people together by factors that don't necessarily make them

alike. The more data we can access -- and one of my roles is I am on the

IITP Inmate and Incarceration and Transition Plan Design Committee. IITP

is this wonderful program that has been designed by the Department of Corrections

-- and you will see why it connects to your question in a minute -- which

assesses needs of inmates as they come into the prison system along at

least seven axes, including substance abuse, mental health, physical health,

vocational training, education and so forth, and keeps track of that data,

makes a plan for them in prison, times it out, it's basically a project

plan for them, what they should do be doing. One of the things I want to

do with that data is exploit it in the warehouse, so that we can start

profiling people about the nature and extent of their drug involvement

and the other factors that are variable, so we can start seeing which things

work best on which people, instead of treating everybody -- the "drug package"

is a standard condition of probation, recommended in very drug case. Well,

for some people and probably for most, it's a perfectly rational thing

to do. For others, it's just there because that is what we do; we make

no attempt to divide people. I believe firmly that (sentencing support

tools will be) very powerful, it just hasn't been used yet. It will be,

and you can always assess it because the data will be there.

Q: Could we think of this scheme as a hyper-sophisticated sentencing

guidelines, where you are very finely defining which box it is we are going

to put the offender depending upon all the factors that the computer knows

about the background.

A: Yes and no. On the one hand, it very much more finely categorizes

people for some information about what you might want to do with this person.

On the other, it doesn't purport to cover all of the circumstances that

should contribute to a sentence. What the guidelines tell you is stay here

unless there's a damn good reason for leaving. What this does is say this

is what has happened to people who are similar, if they are really similar,

when we did these things to them. Now that doesn't mean -- and again, this

is only the recidivism reduction part -- assuming the person is like that

person, one of the things that you want to argue is, is this person really

fairly characterized by what we can find out about similar offenders. So

yes, it's like the guidelines in that it is much more finely categorized;

No, it is not like the guidelines in that it doesn't purport to cover all

the purposes of sentencing, or to have all the information. My frustration

with the guidelines -- I spoke about this when they were first under discussion,

and been critical of the guidelines for this purpose all along -- the guidelines,

for example in serious cases don't distinguish psychopaths from non-psychopaths,

and if you know anything about psychopathy, you want to know that if you

are sentencing somebody on an assault. We treat people identically if they

fit in that box. And another thing that frustrates me about the guidelines

is they are not focused on reducing recidivism. They are a very strange

mix of just desserts and prison beds. Again, by gettoing dropped on my

head I lost the ability to follow the tune too far. I am not sure that

modulating prison bed use is the ultimate question in criminal justice.

It seems to me that the ultimate question is reducing victimization that

can be avoided. and reducing oppression of the fodder for the criminal

justice system which isn't productive of public safety; and sending to

programs that can help people the people they can help; not sending anybody

to programs that they can't help; and using prisons most effectively on

the people who need to be locked up either because we can't ever trust

them outside æcause they're dangerous -- which is a substantial and

important hunk of our people -- or while we deliver to them the programs

that will make them safe to be in the community. That's what we need to

do, and we need a rational approach to do it, and this program is primarily

designed to insist on a rational approach, in the courtroom, pre-trial

release decisions, probation decisions, correctional counseling decisions,

and the same stuff for policy decisions about what categories of sanctions

we ought to support, what programs ought to be promoted with public expenditures

and so on.

Now

I'm not connected to the database. What I'm about to show you is just a

demonstration of how it works. It's not actually working, although the

screens that you will see are actual screens from actual queries against

real data. The piece that I'm proposing and promoting, and the one that's

growing I think state- wide, very slowly, but growing, is the Sentencing

Support Tool. The way it works for judges is that typically you would enter

an OJIN number -- you can select any of a great number of identifiers --

you can use a name and search if you don't have a number -- and the case

number. The way our court system works is that the [OJIN]

Now

I'm not connected to the database. What I'm about to show you is just a

demonstration of how it works. It's not actually working, although the

screens that you will see are actual screens from actual queries against

real data. The piece that I'm proposing and promoting, and the one that's

growing I think state- wide, very slowly, but growing, is the Sentencing

Support Tool. The way it works for judges is that typically you would enter

an OJIN number -- you can select any of a great number of identifiers --

you can use a name and search if you don't have a number -- and the case

number. The way our court system works is that the [OJIN]

For

example, you will recall that we are sentencing this defendant for a Theft

II. So the program defaults to comparing only those people sentenced for

property crimes. You can change that [under the "Charge" tab]. What

we know about this defendant is lurking under the "Profile" tab. And what

we've done, and I think this is an innovation which is itself pretty important

-- criminal histories vary, and it's not just whether they're felonies

or misdemeanors, or how [frequent] they are, but they vary according to

themes. Some people are property criminals with drug involvement, some

have drug involvement with sex crime involvement, some are violent, some

are not, and so forth. We've established data rules for each of six categories,

ranking people from "none" to "severe" in crimes of violence, sex crimes,

drug crimes, property crimes, DUII/major traffic, and domestic violence

crimes. These crime themes boxes are calculated based on what the databases

contributing to the warehouse know about this offender. the Criminal History

score, here, is gathered from the last occasion on which the person received

a sentencing guideline under the regular "criminal history" [as designated

under the sentencing guideline rules]. This offender is 18, or that's what

we understood coming into this [this graphic shows other age boxes checked

by a user; it began with only the 18-20 box checked], and we know his ethnicity.

For

example, you will recall that we are sentencing this defendant for a Theft

II. So the program defaults to comparing only those people sentenced for

property crimes. You can change that [under the "Charge" tab]. What

we know about this defendant is lurking under the "Profile" tab. And what

we've done, and I think this is an innovation which is itself pretty important

-- criminal histories vary, and it's not just whether they're felonies

or misdemeanors, or how [frequent] they are, but they vary according to

themes. Some people are property criminals with drug involvement, some

have drug involvement with sex crime involvement, some are violent, some

are not, and so forth. We've established data rules for each of six categories,

ranking people from "none" to "severe" in crimes of violence, sex crimes,

drug crimes, property crimes, DUII/major traffic, and domestic violence

crimes. These crime themes boxes are calculated based on what the databases

contributing to the warehouse know about this offender. the Criminal History

score, here, is gathered from the last occasion on which the person received

a sentencing guideline under the regular "criminal history" [as designated

under the sentencing guideline rules]. This offender is 18, or that's what

we understood coming into this [this graphic shows other age boxes checked

by a user; it began with only the 18-20 box checked], and we know his ethnicity.

Let me go to what

I think is at least responsive to the question of uniform recidivism measures.

Because this offender is a property offender, the program decided to start

with a measuring recidivism by a conviction for a property crime within

three years of the sentence that it is comparing. And this little window

right here selects the slice of data that you are looking at -- by default

it is 1988 and 2000.

Let me go to what

I think is at least responsive to the question of uniform recidivism measures.

Because this offender is a property offender, the program decided to start

with a measuring recidivism by a conviction for a property crime within

three years of the sentence that it is comparing. And this little window

right here selects the slice of data that you are looking at -- by default

it is 1988 and 2000.