| In the course of promoting data-driven approaches to sentencing decisions,

I have encountered common questions. In all candor, I've responded to some

good questions without first determining that they have become frequent

-- on the assumption that if I encounter a good question, others may have

the same question without it coming to my attention. In any event,

I hope the following answers will help to explain the nature and benefits

of this technology as applied to criminal justice. For further information

or to offer comments, please

send

e-mail.

Q: What is "smart sentencing"?

Q: Can sentencing be "smart" without

technology?

Q: Do

you want computers to make sentencing decisions instead of judges?

Q:

Haven't recent ballot measures and statutes eliminated the role of discretion?

Q.

How can you be so disloyal to your colleagues by blaming them for crime?

Q: How does Blakely v. Washington

affect all this?

Q: What happened at the ALI annual meeting

in May, 2007?

Q:

Is it really a good idea to have judges try to predict which sentences

will work best to reduce criminal behavior?

Q: Are you

trying to replace probation officers?

Q: Isn't unrealistic

to expect lawyers who practice criminal law to handle data and research

about what works?

Q: Smart sentencing makes a

lot of sense; what are the arguments against it?

Q: Is this all an argument

not to use jail or prison?

Q: Aren't

you shifting responsibility from criminals to the courts when you blame

the courts (or criminal justice) for recidivism?

Q:

Are you saying retribution and general deterrence should be discarded as

objectives of sentencing?

Q: How

can you expect providers accurately to gather and report the data you need?

Q:

What makes you think this technology will serve public safety?

Q: What impact

do you expect to have on recidivism?

Q: Don't we already know what works?

Q: Why

can't we just exploit the research we already have?

Q: How

can you evaluate programs with limited access to their internal data?

Q: Are you

trying to replace research and researchers?

Q:

Does this sentencing support technology have any other benefits for criminal

justice?

Q: Why include

ethnicity in the offender profile?

Q: Is it fair to include

gender and other variables the offender cannot control in the profile?

Q: Is anyone else doing

this now?

Q: Have you determined that

your results are statistically significant?

Q: How

do you know outcomes don't reflect accurate predictions rather than cause

and effect?

Q: Doesn't

plea bargaining distort the data?

Q: Isn't

this just a fancy risk assessment tool?

Q:

Haven't the experts concluded that nothing really works?

Q:

How can you expect offenders to change until they're ready to accept change?

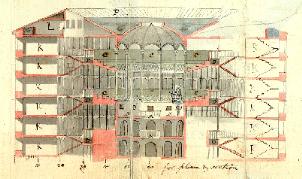

Q: What is that graphic you use

on so many pages?

Q: What is "Smart Sentencing?"

A: Some have asked what I mean

by "smart sentencing" and ask for examples. For my purposes, "smart

sentencing" is sentencing that rationally seeks to accomplish an objective

-- usually reducing the likelihood that an offender will commit future

crimes, but the concept can apply to any sentencing objective. Sentencing

rationally seeks an objective whenever it uses best efforts to access relevant

information about the sentencing choices available for an offender.

Sentencing support tools are but one source of helpful information.

Within limits, these tools tell us what has happened (in terms of subsequent

criminal behavior) to similar offenders, sentenced for similar crimes,

who received any of the dispositions available for the offender now being

sentenced. Of course, "similar" is hardly the same as identical,

and depending upon the size and nature of the cohort of offenders, the

precision with which we've identified truly similar offenders may vary

greatly. Even with an "identical" cohort based on the data available

to the tools, variables not recognized by the tools [because they are not

routinely collected and shared -- or even known to the system] may make

one offender more or less likely than another within the cohort to benefit

from a given disposition.

Here are two examples. Traditional sentencing might

simply take a low level theft offender with a record of low level thefts

and routinely impose a period of, say, 18 months bench probation, "theft

talk," and a fine of $150 plus fees and assessments. Smarter sentencing

would look at what similar offenders, of a similar criminal background,

age, and gender, did after receiving any of the available dispositions.

With no other information, and no reason to suspect some individual characteristic

that makes a difference, smarter sentencing would consider doing what seemed

to work best in the past on such offenders for such crimes. For some

cohorts, by the way, I've seen that anger management correlates substantially

better than traditional theft sentences with reduced recidivism, and for

such a cohort, I might well consider adding anger management (or substituting

it for a fine). If we had the resources to do a criminogenic assessment,

we might find a connection between substance abuse or a mental health issue

and the criminal behavior -- if so, smarter sentencing might involve addressing

the substance abuse and mental health issues with a dual diagnosis treatment.

On the other end of the spectrum, traditional sentencing

of a sex offender convicted of, say, six separate crimes, might include

120 months prison total, with most of the time running concurrently to

produce that 120 months -- because ten years seems "just" in light of the

crimes. [What is "just" is ultimately a tremendously fluid concept].

Smarter sentencing would look to a psychosexual evaluation to assess the

risk level and susceptibility of the offender to any available sex offender

treatment. In the case of a predatory pedophile, that process might

well suggest that the risk of recidivism is extremely high and the likely

impact of any treatment extremely low. Coupled with literature suggesting

that post-prison recidivism does not increase with the length of custody

for high-risk offenders [the opposite seems to be true with most low and

medium risk offenders], and literature suggesting that such sex crimes

do not taper off with advanced age (as do most crimes), smart sentencing

would seek the maximum consecutive prison sentence and probably arrive

in the vicinity of over 500 months in prison.

Sentencing support tools show that for some female

drug offenders, even those for whom prison is usually employed because

they have multiple prior offenses, parenting classes are apparently

more successful than custody for preventing new crimes. Looking at

and considering all of the information about what works on whom and making

our best efforts to do that which is most likely to work -- responsibly

in light of the nature and the extent of the risk to the public, both in

the short and in the long run -- may well call for parenting classes instead

of prison.

Smart sentencing is evidence-based, responsible,

and accountable; it employs our best efforts to accomplish what the public

expects us to accomplish: crime reduction. At the same time, it is

kinder both to the potential victims smart sentencing will prevent, and

to offenders who can be diverted from criminal careers -- who, without

smart sentencing, would be repeatedly cycled through the criminal justice

system and punished with no benefit to them or to the community their behavior

offends.  return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q: Can sentencing be "smart" without

technology?

A: Yes. Sentencing support technology

is an important means by which to get useful information to the process,

but its ultimate purpose is to get the process to employ best efforts to

achieve public safety and any other relevant and legitimate purpose of

sentencing. The Oregon Judicial Department has recently revised our

Judges'

Criminal Law Bench Book (which is available on the Supreme Court Library's

web page) to include an expanded chapter on sentencing. The first

thirty pages or so of that chapter (starting on page 727) are devoted to

practical tips to assist in making informed and effective sentencing choices.

For example, if a probation officer or district attorney is urging imprisonment

to ensure that a repeat low-level offender finally gets drug treatment,

the tip is that we need to gather the information about the actual availability

to the offender in question of drug treatment in custody. Testing,

challenging, and questioning routine assumptions is smarter sentencing

than sentencing based on guesswork and empty assumptions.  return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q: Do

you want computers to make sentencing decisions instead of judges?

A: No. The computer simply gives

the decision maker vastly improved access to important information - such

as how similar offenders have fared after being sent to or serving sanctions

or completing programs available for this offender. This helps the decision

maker make more informed decisions about how best to try to reduce this

offender's future criminal behavior, but it does not even address the other

components of sentencing. And even within the goal of reducing this offender's

criminal behavior, there is much left to advocacy, analysis, and individual

assessment.

Sentencing support tools do not purport to

display causation or to factor in such important variables as offender

risk and need. The tools' primary purpose is to raise the "what works?"

question by giving easy access to outcomes for similar offenders sentenced

for similar crimes -- to focus sentencing attention on outcomes.

They will have served their primary purpose when the routine discussion

becomes what is most likely to work and why, with the tools serving

only their secondary function: providing accurate data on outcomes correlated

with similar offenders and crimes -- so the participants can address why

that information is or is not predictive for the offender in question.

At a recent law class, a student asked what the

"end stage" of this effort would look like. Of course, the future

is impossible to predict, but I envision a criminal justice system that

approaches sentencing much as modern public health agencies approach disease

-- cognizant of the wide range of human behaviors, qualified by the limitations

of human bureaucracy and finite resources, but competently and rationally

addressing a persistent and changing challenge to the quality of life in

our communities with responsible use of available information and appropriate

techniques.  return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q:

Haven't recent ballot measures and statutes eliminated the role of discretion?

A: No. By far the most numerous

cases in our system are less serious crimes which are not covered by mandatory

minimum sentences or even by the sentencing guidelines that apply to felonies.

The guidelines allow for departure to serve compelling and substantial

interests, but even for those cases subject to mandatory minimum sentences,

judges have tremendous discretion to impose greater sanctions than

those required. They frequently have discretion whether to impose consecutive

or concurrent sentences. And in the great majority of cases, judges have

wide discretion whether to impose incarceration or probation with conditions,

to structure conditions of probation and to recommend programs during incarceration,

and whether and when to revoke probation or to continue probation with

modified conditions. Without sentencing support technology,

all of these decisions are commonly based on ideology, philosophy, or faith;

they are almost never made based on (or even with access to) information

about how similar offenders have behaved after being subjected to similar

choices in the past.  return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q: How does Blakely v. Washington affect

all this?

A: Not much. Blakely

v. Washington and its progeny have spawned expansive debate about

how to accommodate a right to jury trial attached to facts essential to

enhanced sentences. United

States v. Booker confirmed the fears of Professor Kevin Reitz and

other advocates of a guidelines centric rewrite of the Model Penal Code's

sentencing provisions: an easy fix is to deem guidelines merely "advisory."

While guidelines advocates and the other major players scramble to modify

sentencing forms to respond to Blakely, each segment of the sentencing

debate threatens its own objectives by pursuing a strategy that ignores

crime reduction - the major function of sentencing rightly sought by the

public. There are other easy fixes - including the simple provision for

a jury trial where required, as urged in Justice Stevens' opinion in Blakely.

Any response that merely continues the sway of guidelines that are blind

to public safety will only resume the tragic cycle of misdirected sentencing

decisions, avoidable victimizations, responding restrictions on sentencing

discretion and expanding demand for draconian sentencing. But any

fix will probably either restore or expand sentencing discretion -- even

without a fix, the only discretion lost is that to depart above a discretionary

range without first affording the defendant a right to a jury trial on

facts critical to sentence enhancements. So all of the argument for

using whatever discretion remains to achieve best efforts at crime reduction

survives Blakely. return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q.

How can you be so disloyal to your colleagues by blaming them for crime?

A: I should start by revealing that

I have enormous respect for my fellow judges. In my many years of

working with them (I was appointed to the bench full time in March, 1990,

and practiced before the same courts for 16 years before that -- and another

four in California), I have learned that performing quality, impartial,

and valuable work in our public function is the ambition of virtually all

judges I know. Many of my colleagues go the extra mile for public

purposes in addition to the requirements of the cases on which we sit.

Many volunteer many hours to the administration of justice – writing articles

and presenting legal education courses for law students and lawyers, serving

on many committees devoted to improving the law itself or the processes

of the courts, and speaking to groups of citizens who want to know about

the courts and the law. Through such efforts, and in cooperation

with bar associations, legislative committees, and public and private agencies,

judges I know work to reduce child abuse and domestic violence, improve

the foster care and adoption systems, reduce barriers to people who cannot

afford attorneys to represent them in legal proceedings, help parties settle

existing cases without the emotional and fiscal expense of trial, support

recovery from addiction, assist victims impact panels in their attempts

to convince drunk drivers not to repeat their mistakes, and help women

offenders earn back custody of their children. A good number of judges

go

to great lengths to make treatment courts work, and to follow up with probationers

to improve their chances of leading productive lives. I am proud

to say that my colleagues voluntarily created a fund in response to our

recent budget crisis to alleviate the hardship of court staff whose mandatory

furlough days put them in financial crisis. For these and many similar

reasons, I consider myself fortunate indeed to be a part of such a group

of colleagues.

But it is in the nature of and human beings

and social processes that good people, pursuing normal routines with skill

and the best of intentions, sometimes persist in behaviors that tolerate

or even cause harm -- yet resist scrutiny, measurement, or change that

might imply that they are somehow responsible for outcomes they surely

never sought. It's easy to see this scenario in other times and places,

but often difficult for any profession to contemplate such notions in their

own time and place. This institutional denial explained the expulsion

of Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis

from Vienna because he learned that having his medical students wash their

hands between dissections and deliveries drastically reduced maternal mortality.

His hospital employer simply couldn’t accept the message that business

as usual had been killing patients. It was not that his colleagues

were not committed to the ideals of their medical calling, but that human

institutions have enormous capacity for denial.

More recently, the Institute

for Healthcare Improvement tackled the problem that was costing the

loss of hundreds of thousands of lives through mistakes in hospitals (at

a rate of 98,000 per year – plus millions of non fatal mistakes), and eventually

produced tremendous success in reducing such errors through procedural

changes. The present point is that neither the certainty of professionals

that they are well intended and competent, nor the outrage of their defenders

when others suggest that the status quo is killing people, protects those

who suffer unintended harm at their hands nor answers the need for change.

Mainstream sentencing is governed by plea

bargains that generate 90-95% of sentences with little or no judicial intervention.

Outside the treatment courts, we judges permit punishment for its own sake

to dominate the discussion, and we allow the enormously elastic goal of

proportional punishment alone to constitute adequate performance – largely

ignoring, but surely never measuring, crime reduction or any other social

objective.

Most offenders sentenced for most crimes offend

again, and most horrible crimes are committed by offenders repeatedly sentenced

in the past with no responsible effort to reduce the offender's criminal

behavior. Because we're not doing our best to focus sentencing on

crime reduction -- because we're giving punishment per se complete control

of the process without making any effort to ensure that even the legitimate

purposes of punishment are served -- we are tolerating tremendous unnecessary

brutality: avoidable victimizations smarter sentencing would have prevented,

and often draconian sentences imposed on some offenders with no hope of

serving any social purpose.

The tragedy is that good people with good

intentions can produce such results. The compounding tragedy is that

judges sometimes bristle at the very goal of "improvement" because of its

implications for current performance, and resist performance measures on

any number of grounds if the performance measures touch on our impact on

harm reduction. The final irony is that we often expect far more

insight and accountability from the offenders we sentence than we are willing

to adopt for ourselves.

Of course, changing the status quo requires

avoiding rather than confronting the denial. Those who want to change

things need to convince others of the urgency of the need for change, but

once there is a sufficient number of judges and others committed to change,

the trick is finding tactics that work without conveying criticism or blame,

but instead tap the enthusiasm for contributing to the public good that

motivates so many in our role

Unfortunately, there are a substantial

minority of judges who actually argue that crime reduction is not our job

-- but that's another story.  return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q: What happened at the ALI annual meeting

in May, 2007?

A: The short answer is that the

motions were all defeated, a not unexpected outcome given the deference

that the process effectively gives to the reporter in projects, and the

cultural depth of acceptance of retribution regardless of function.

It is hard to untangle the process from the result. There was substantial

testimony from people unknown to me in favor of the first motion (to restrict

the role of retribution both by proportionality and by some plausible connection

to any social purpose served by punishment), but the discussion soon became

clouded by the reporter’s suggestion (whether or not intentional) that

my motion would add roles for retribution rather than limit them as compared

to his draft. I suspect that many who voted were at least confused

and at worst assumed that proportional severity serves only to limit utilitarian

functions in the reporter’s draft. Critically, that misses the point

of the debate. Under the draft, which is now set virtually in stone

by the vote at the annual meeting, a sentence may properly punish for its

own sake regardless of any pursuit of any purpose as long as the punishment

is “proportional” by just desert standards – meaning within the range of

presumptive sentences promulgated by a sentencing commission. The

point of the motion was to limit punishment per se to occasions on which

it plausibly serves to promote public values in the specifics articulated

in the motion:

The struggle for a more rational sentencing

structure and practice continues. There are provisions in the MPC

yet to be refined that have a role in this. And there are efforts

underway at the national level that intend to shift the culture of sentencing

away from ordered just deserts to evidence based practices.

The MPC draft will squander an opportunity to provide real leadership,

but may yet be of some assistance in the right direction. return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q:

Is it really a good idea to have judges try to predict which sentences

will work best to reduce criminal behavior?

A: In my quest, I have occasionally

encountered the view that judges have no business trying to adjust sentences

based on their impact on the offender's criminal behavior. I think

it fair to say that on all occasions, the majority of those who heard such

comments were as astonished as I was, but the view that sentencing is about

something other than reducing criminal behavior is actually consistent

with the almost universal behavior of participants in the sentencing process,

so this question merits a response. First, the data from Multnomah

County's sentencing support technology clearly shows (as does an enormous

quantity of criminological and correctional research) that different dispositions

have different correlations with future criminal conduct -- that some sentencing

decisions are in fact at least not preventing future victimizations by

those sentenced as well as other decisions. It is obviously foreseeable

that paying attention to what works on whom and what does not can make

a difference in the likelihood of future victimizations, and in most other

areas of the law, consciously ignoring a substantial risk of harm is equated

with recklessness and the potential for civil or criminal liability.

In other words, claiming that the public safety consequences of our decisions

are not are our responsibility is simply untenable; we produce those consequences

whether or not we cling to denial. And in any logical world, continuing

not to try to do a better job is obviously far more risky than making our

best effort to produce better outcomes.

Second, at least in Oregon, the 1996

amendment to Article I, Section 15 of the Oregon Constitution (quoted

in 1997 Oregon Judicial Conference #1), and

1997

HB 2229 have settled the issue: public safety is a goal of sentencing.

Third, those who argue against sentencing based

on prediction of future dangerousness tout the "false positives" such predictions

often produce or, from the other end of the spectrum of those suspicious

of data-based sentencing, the "false negative" represented by an offender

who is released on a prediction of safety which proves tragically erroneous.

This misses many points: arguing that sentencing should not even try to

focus on crime reduction avoids the measure of success -- it does not improve

success. Pretending we are sentencing for some other purpose than

public safety, or pretending that we are not attempting to predict future

dangerousness when we incarcerate for the longest terms those with the

worst crimes and the worst records, does not change the percentage of people

we put in jail for longer or shorter terms than necessary for public safety.

Following this path doesn't improve our rate of false positives or false

negatives based on public safety, it just justifies these errors by pretending

that the purpose isn't public safety to begin with. We should do

better at using sentences intelligently if we make the effort than if we

do not. And as long as the offender has been convicted of a crime

and the sentence is not otherwise disproportionately severe, that a violent

offender only has a one in three chance of assaulting, raping, or murdering

another victim hardly argues against his incapacitation. As to the

risk of "false negatives," it is inevitable throughout the process that

the length of terms of incarceration for most offenders [the vast, vast

majority] will be quite limited. Whether it is a pretrial release

decision, a decision whether to render sentences consecutive or concurrent,

whether to revoke a probation, or whether and under what circumstances

a correctional authority ought to allow an inmate some reduction in the

duration or nature of confinement, we surely are more likely to produce

more false negatives if we decide based on something other than

risk prediction; surely the path to public safety lies in making these

decisions as knowledgeably as we can. Insisting that offenders not

be released at all, that they be imprisoned in every case as long as the

law allows, and that there be no offenders whose term is somehow ameliorated

at the far end does not serve public safety as long as the reality includes

such releases, sentences, and ameliorations. And almost 80% of our cases

are misdemeanors, and very very few produce the maximum one year incarceration

-- our jails are typically "matrixing" people simply because we have no

where near enough beds to lock everyone up who has been sentenced for as

long as their sentence! As to felonies, our guidelines restrict actual

custody time for the majority of cases to even less than is theoretically

available for a misdemeanor; even by departure, the lower felonies cannot

even exceed a six month term. The vast majority of felons in

prison will return to their communities. It is only when we get to

the most serious crimes and criminal histories that significantly longer

that a year an a half to a few years is available for incarceration.

To see the Oregon guidelines, click

here. return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q: Isn't unrealistic

to expect lawyers who practice criminal law to handle data and research

about what works?

A: No. The underlying concern

is that lawyers, particularly criminal law practitioners, are accustomed

to a high volume, fast-paced, flow of cases and hearings and are ill-equipped

to master data or research about what works and to be useful to the court

in the style of practice to which they've become accustomed. There

are, of course, several responses:

Although express attention to what works is rare

indeed within the style of criminal justice to which we've become so unfortunately

accustomed, it is not completely missing. In the wide range of occasions

and approaches to sentencing, there are certainly those that now involve

a lawyer attempting to inject what we allegedly know about what works into

a hearing in an attempt to persuade the judge in favor of that lawyer's

goal. At the high volume end of the spectrum, a defense attorney may assert

that keeping the defendant employed will lower his risk of recidivism so

that any jail sentence ought to be brief or served on weekends; the prosecutor

may respond that the defendant's criminal history demonstrates that employment

hasn't kept this offender from offending, so that a long sentence will

at least keep him from offending while his is locked up. The judge might

explore whether the need for tight supervision and the general value of

continued employment militates in favor of work release. It is a

sad measure of how far we are from responsible pursuit of crime reduction

that increasing the frequency of even this level of debate would

be a profound improvement in sentencing culture, and likely productive

of improved sentencing outcomes. And encouraging attorneys by the

frequency of this discussion, and the interest it receives on the part

of the sentencing judge, gradually to increase their fluency in the data

and literature which improves the accuracy of either assertion as applied

to a given offender, crime, criminal history (and, for that matter, cluster

of criminogenic factors) does not require a sea change in skills, intelligence,

or preparation. For high volume cases, this would require no greater

effort or time on the part of practitioners and courts than the constant

infiltration of new information about laws affecting suppression motions,

appellate decisions and legislation affecting common crimes, and the loss,

modification, or addition of sentencing options -- including, by the way,

information about how long a given offender is likely to serve if sent

to a "jail" sentence. The nature of the beast is that all of us have

to stay up to date on a wide range of matters to retain minimal competence

at this task, and that gradually including and then upgrading competence

about what works best on which offenders under which circumstances would

hardly overtax the people or the system involved.

As a practical matter, it is at least immediately

unrealistic to expect high volume criminal practice attorneys to carry

around notebooks (or the electronic equivalent) of studies, articles, and

literature reviews to cite to each other and to the court on routine sentencing

debates. But attorneys and courts are quite adept (often too much

so) at capturing, distilling, and exploiting relatively common notions

that are useful for the debate in the high volume cases. Literature

and study based notions are already there: full time employment or

school favors crime reduction for many offenders; domestic violence offenders'

potential lethality can be roughly guessed based on factors known to most

practitioners (especially, whether the victim is attempting to get away);

addicted offenders with heavy use patterns are unlikely to get anywhere

for our benefit or for theirs until and unless their addiction is addressed;

jail keeps people from committing crimes on the outside while they are

in the inside. These notions, though hardly a substitute for thorough

criminogenic assessment and risk prediction, are also far from useless.

Again, just increasing the occasions on which wielding them may affect

the result because of the court's focus will encourage the gradual improvement

in their wielder's knowledge and usefulness in informing an outcome productive

of public safety.

In Multnomah County, our sentencing support tools

generate data about what has or has not correlated with crime reduction

by an offender cohort similar to any offender considered for sentencing,

when sentenced for a similar crime. These tools are available to

judges and attorneys; using them has a relatively slight learning curve.

A moderately experienced user can come up with some useful information

for most offenders in under five minutes. I regularly generate charts

during most sentencing hearings; the ensuing discussion is what may take

a few minutes of additional time. We do not turn ten minute sentencing

hearings into half day proceedings; we may push some from ten to twenty

minutes if the issues are difficult. Lawyers seem to have no difficulty

analyzing and challenging the information and its relevance to the decision

at hand.

At the higher end of the spectrum, lawyers are already

expected to be able to handle psychological evaluations, criminogenic risk

assessment, and similar issues with competence in the death penalty and

dangerous offender (and sexually dangerous offender) contexts. This

is a function they take to just fine -- as do their brethren on the civil

side who come with a legal training and, typically, a liberal arts undergraduate

degree, to expert disputes of the highest sophistication involving virtually

every science and literature known to the wide world of malpractice, environmental,

product liability, and intellectual property litigation. The same

judge you may think unsuited for risk prediction in the criminal area may

well be sitting on and deciding cases on the civil side involving whether

there is enough basis in the literature to let a jury hear some expert

give an opinion about a medical procedure, the adequacy of error detection

mechanisms to cope with the products of incineration of Sarin chemical

agent, the adequacy of file encryption technology afforded under a contract

for computer security services, or the propriety of treating depression

with a particular mix of drugs and electro-convulsive therapy. Indeed,

the same judge may already be making risk prediction decisions based on

the literature of psychopathy in dangerous offender proceedings.

And the lawyers in all of these proceedings are expected to be competent

(and quite usually are).

By the way, it is among the greatest triumphs

of social evolution that court proceedings and the adversary process is

fully capable of taking the most renowned and published experts in a field,

pitting them against each other through examination and cross examination

by counsel, and testing their wisdom in this crucible to produce a more

reliable or at least a more practical application of their learning than

they would ever accomplish in the journals that otherwise quietly contain

their debate. This process is not without its faults, but as many

have said repeatedly, it is the best we've yet devised. It is also

fully capable of producing the best results from the debates among academics

and others about what works best to reduce crimes among which offenders.

To return more closely to the topic at hand, I think

it clear that we don't need notebooks full of journal copies before high

volume practitioners can be more often useful and informed about what works

best in the most common cases, and that lawyers and the system already

demonstrate their capacity for journals, studies, literature, and experts

on occasion at the other end of the spectrum represented by dangerous offender

and death penalty proceedings. That smart sentencing would encourage

more information into the process probably means that more of those involved

would indeed gradually have to learn more about what works as time goes

on. There is a lot of hot air and spouting that can be displaced

without any loss to anyone (except, perhaps, those who savor the tragic

comedy of claptrap followed by recidivism that smarter sentencing would

have avoided). And it would be no great disruption or imposition

to add to the culture of practitioners and judges, which now includes notebooks

and continuing education hours covering such topics as search and seizure

law, notebooks and continuing education hours on best sentencing practices.

(Judges and lawyers already have some opportunities for hours on best practices

and best advocacy techniques related to sentencing hearings)

Here, as in so many areas of objection, the

bottom line is that the system could well do a better job than it now does

without violating its paradigms, including those of personnel and training;

that we now so rarely attempt responsible smart sentencing that there is

much room for public safety improvement without significant increases (but

only minor redirections) of time and energy among practitioners and the

courts; and that even if and when it takes some real time and energy from

our participants both the reduction in avoidable victimizations and the

reduction in repetitive drains on recourses by recidivist offenders are

more than enough to justify those increases.  return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q: Smart sentencing makes

a lot of sense; what are the arguments against it?

A: It's been surprisingly hard to ferret

out real arguments against the notion that we should do a more responsible

job of crime reduction when sentencing people by trying to focus on what

works on which offenders. Most of the contentions are either withheld,

or implied indirectly in the questions I have attempted to answer elsewhere

on this page. I have tried to elicit some direct answers from the

author of the proposed revisions to the Model Penal Code, Prof. Kevin Reitz.

His proposal represents a profound retreat from the present MPC sentencing

provision which emphasizes public safety, and I have published substantial

comments arguing that this is the wrong decision. Comments on

the Model Penal Code: Sentencing, Preliminary Draft No. 1, 30 American

Journal of Criminal Law 135 (2003) [University of Texas Law School], [Available

on WestLaw at 30 AMJCRL 135.] After a long telephone conference with

Prof. Reitz, I sent him a letter outlining what I understood to be our

agreements and our disagreements, and asking him for confirmation or explanation

as to where and why we disagree. A copy of that letter (sent in October,

2003), is here:  Prof. Reitz has never responded.

Prof. Reitz has never responded.

I have elicited some direct contentions

from various significant actors in the criminal justice field in Oregon.

Here's what I have learned so far:

From a principal author of Oregon’s

Sentencing Guidelines (and past Attorney General of Oregon):

1) There are other purposes of sentencing

besides preventing recidivism, including punishment.

A: Of course there are. But the

recidivism

statistics make it clear that we are doing an awful job of reducing

recidivism. We don’t have to reach agreement as to the relative importance

of punishment per se, restitution, or general deterrence to agree

that we aren’t doing much to attempt crime reduction, and that we should

be able to do a much better job if we made a responsible attempt. And smart

sentencing assesses incapacitation, specific deterrence, and “rehabilitation”

in looking for what works best on which offenders.

2) Wouldn’t focusing on what works

on which offenders result in disparate treatment, and wouldn’t that undermine

the benefit of the guidelines in avoiding unequal treatment?

A: First, Oregon law already

recognizes that differences in amenability to rehabilitation justifies

different responses to offenders. ORS 161.025(1)(a), derived from

the existing (1962) Model Penal Code, declares the purposes of the Criminal

Code as including "To prescribe penalties which are proportionate to the

seriousness of offenses and which permit recognition of differences in

rehabilitation possibilities among individual offenders." Equal treatment

means that people similarly situated should be similarly treated.

There is no reason doing more dependably what works on the offenders it

works on is inconsistent with similar treatment for similarly situated

offenders, unless of course one community has something that will prevent

recidivism by a given offender, when another community with an identical

offender lacks that sanction, treatment, or other disposition. I’d

argue that the availability of such a sanction, treatment, or other disposition

is a difference that makes the offenders not equally situated, so that

the disposition is not inconsistent with similar treatment of similarly

situated offenders. In any event, I have not yet encountered anyone

who would actually argue that we should deprive the public of the protection

of the sanction, treatment, or other disposition that works just because

we don’t have it in every community and can’t apply it to all offenders.

A: Second, the guidelines’ achievement

of equal treatment is far from ideal. We maintain the illusion of

equal treatment by refusing to acknowledge differences in offenders, criminal

histories, crimes, or available sanctions to insist that we are treating

equal offenders equally. Thus a one-time remorseful assault perpetrator

ends up with the same presumptive sentence range as someone who committed

an identical crime with the same criminal history – but is a psychopath.

And the economic categories that separate the crime seriousness ratings

for property crimes offend even just deserts – why should the theft of

a Rolls Royce whose owner rarely sees it in his stable of luxury cars be

punished more severely than the theft of a clunker that provides a single

parent her only means of transportation? Similarly, the guidelines

ignore the tremendous variety that can exist among equally rated

criminal histories (two prior person felonies by a psychopath who intended

the harm he caused will be treated exactly the same as two prior person

felonies by a remorseful bar brawler who barely lost self-defense arguments

because his response was more than reasonable). Of course, we can

attempt

to accommodate these variations with departures, but departures are exceptions

to the equal treatment invoked to defend the guidelines against improvement

for crime reduction.

A: Third, given our consistently poor

crime reduction performance, is it even clear that consistency is a good

thing?

From a prominent Oregon District Attorney:

1) Some fear that smart sentencing would

displace other purposes (such as punishment).

A. Again, to be smarter in sentencing we

don’t have to abandon all objectives other than crime reduction.

Let’s be direct here: Crime reduction is usually ignored, sometimes assumed

without any more support than mere ideology or guesswork, but almost never

responsibly pursued in sentencing. Whenever we do something instead

of smart sentencing we are reducing the chances that we will reduce or

prevent future criminal conduct by the offender. Our sentences will have

a public safety outcome regardless of whether we do our best to achieve

crime reduction; any argument to do something else amounts to an argument

not to do our best. To that extent, we are complicit in avoidable

victimizations.

2) Sentencing based on data and research would

interfere with the flow of plea bargains.

A. This has at least two components: administrative

efficiency and control of plea bargain outcomes. With respect to

administrative efficiency (how much time it takes to negotiate and dispose

of a case), revising some of the components of the process with smart sentencing

does not have to make things take longer. Just as most cases are routinized

around just deserts and resources, with a discount for witness difficulties

or a search and seizure vulnerable to a motion to suppress, we could make

a lot of progress more rigorously routinizing cases around crime reduction.

Moreover, doing a better job of avoiding future victimizations is worth

some additional time in processing cases. Finally, the biggest waste

of time and resources is the sentence that fails to divert an offender

from criminal behavior which again taxes the time and resources of the

criminal justice system. 304 of the 372 offenders jailed

for drugs in July 2000 in Portland were in the jail within the prior

year on some other occasion.

With respect to the issue of the prosecutor’s control

of plea bargaining outcomes – both with respect to the defense and to the

court’s role, inserting smart sentencing has no inherent impact on that

control. In other words, were the prosecutor to negotiate around

crime reduction based on data and research, the issues whether the judge

would avoid tinkering with the deal or the defense avoid ameliorating it

when in front of the judge vary not at all from the present situation.

That situation includes that the attorneys are free to employ a “contract

plea” to give the judge the limited choice of accepting and enforcing the

deal as is or rejecting the plea. That situation also includes that

some judges are far more reluctant to tinker with a non-contract plea than

others. Indeed, the more “what works” catches on with judges, the

more likely they are to tinker with a plea bargain that was made without

regard

to what works. In other words, if the parties present the judge with

a deal justified and described in terms of what is most likely to reduce

crime, a “smart sentencing” judge is more likely to leave it alone than

in the case of a deal with no such justification or explanation.

I avoid in this analysis any attempt to resolve the question whether and

to what extent judges should be potted plants when it comes to plea bargains.

From an activist crime victim: Research

and data are overwhelmingly flawed.

A: Yes, much research is flawed, and few

data are completely “clean” of errors. But here’s the thing: we must

always keep the choices in mind – do we endeavor to improve, select, and

analyze the data and research, or do we choose to rely instead upon the

status quo of unformed, essentially a priori debates about what an “appropriate

sentence” should be – mixing aggravation, mitigation, and anything else

that comes to mind? The irony here is that in the face of imperfect

data and research we abandon all attempts at accuracy or evidence-based

decisions, and support the opposite.

If we could achieve candor, we’d see that much of

this argument is really based on a bias for or against punishment, for

or against prison. Just as the incarcerationists bemoan “false positives”

of “preventive detention” (their disparaging name for incapacitation based

on risk assessments) to argue against using jail or prison for crime reduction,

others who criticize data and research for its imperfections ultimately

fear that it will reduce the use of incarceration because they are persuaded

that jail or prison is either deserved or will best produce public safety.

Even beyond the possibility that retribution and crime reduction can be

at odds in crafting a sentence, the problem with this is that the choice

between prison and alternatives, or among terms of jail or imprisonment,

in fact has different public safety outcomes depending on the offenders

(and, often, the conditions of incarceration). Always insisting that

jail or prison is the answer, particularly as to crimes for which only

relatively short periods of incarceration are available, is just as dangerous

as any other faith-based approach to sentencing. We will make more

wrong decisions without good information than with it; we can as easily

cause avoidable victimizations in the long run by choosing jail as by choosing

probation – again, at least at the level of crimes for which jail or prison

terms are relatively short.

To test the notion that faith for or against incarceration

is the real agenda of many who resist smart sentencing based on the imperfection

of research, see how the rigor with which they assail research with which

they disagree compares with the rigor with which they’ve scrutinized any

research or data that supports their favored disposition.

This is not to say that we should be sloppy – far from

it. We must be rigorous in seeking best efforts at crime reduction.

A good way to do that is to make the issue of what works a subject of competent,

informed, and vigorous advocacy in sentencing and probation hearings.

From an academic turned appellate public

defender: I don’t see how the guidelines could be adjusted

to incorporate crime reduction.

A: It’s always amazing to me how powerfully

habits and culture limit our ability to see the obvious. Of course,

it would be a formidable undertaking to structure a set of guidelines that

incorporates all we know and can learn about criminogenic and risk

factors, and all the other variables that might be part of a calculus that

made the presumptive sentence more likely to be predictive of public safety

than under the present guidelines. But we’re capable of formidable

undertakings when the motivation is sufficient. Nanotechnology, molecular

biology, computer science, and modern medicine all regularly employ concepts

far harder to grasp than the two-dimensional sentencing guideline grid.

But we don’t have to undertake a perfect product to make tremendous improvement

in the existing approach, and individualization will always at least potentially

improve any specific sentencing. For starters, we could use any of

the standard violence prediction instruments to make a longer period of

incarceration than currently prescribed by the guidelines presumptive for

violent offenders with a high score. (For a comparison of several approaches

to violence and risk prediction, check this

link). And one state, Virginia, has actually incorporated risk assessment

into its sentencing guidelines after careful and responsible study. See

Brian J. Strom, Matthew Kleiman, Fred Cheesman, II, Randall M. Hansen,

Neal B. Kauder, Offender Risk Assessment in Virginia - A Three-Stage

Evaluation: Process of Sentencing Reform, Empirical Study of Diversion

and Recidivism, Benefit-Cost Analysis (The National Center for State

Courts and the Virginia Criminal Sentencing Commission 2002), available

at http://www.vcsc.state.va.us/risk_off_rpt.pdf.

Critics from the anti-incarceration side will

again invoke false positives, and from the pro-incarceration side we will

hear of offenders whose sentences weren’t enhanced who recidivated in a

horrible way. But the real test is whether we do a better job of

crime reduction with or without this dimension. How many victimizations

are occurring now because we don’t do our best at crime reduction?

As to false positives, we are already working within the realm of incarceration

not disproportionate for the offense already committed; assessing risk

rather than demanding certainty in choosing where within that range to

place a given offender is entirely appropriate. [For dangerous offender

schemes that provide a longer period of incarceration than the maximum

otherwise available for the latest felony, I agree with the critics that

rigor is required (and now imposed by Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530

U.S. 466 (2000)), but I cannot agree that we should not consider longer

sentences for such offenders, that we cannot impose such sentences unless

we can achieve risk prediction with certainty, or that it is somehow better

to reject data and research than to attempt to make our best use of it

with knowledge of its limitations.] Guidelines proponents do not

avoid false positives by rejecting risk assessment -- they compound and

rename them.

From another Oregon trial judge:

Won’t inviting argument and evidence about what works best require lengthy

court hearings and testimony?

A: Replacing some of the components

of the process with smart sentencing does not have to make things take

longer. It doesn’t necessarily take longer to argue what changes

will or won’t reduce an offender’s criminal behavior and what dispositions

are most likely to help [ranging from incapacitation to treatment] than

it now takes to argue aggravation and mitigation, heinousness of the defendant's

behavior and depravity of his childhood. Moreover, even when we chose

to hear from experts through testimony, doing a better job of avoiding

future victimizations is well worth some additional time in processing

cases. Finally, the biggest waste of time and resources is the sentence

that fails to divert an offender from criminal behavior which again taxes

the time and resources of the criminal justice system. 302 of the 374 offenders

jailed for drugs in July 2000 in Portland were in the jail within the prior

year on some other occasion.

For all of the above: None of these arguments

change some basic facts. First, every sentencing decision has a public

safety outcome. Second, although it is less threatening to avoid

accepting responsibility for those outcomes than to pursue “just punishment,”

“equal treatment,” or an outcome whose propriety is based on its proponent’s

ideology, anything other than responsible pursuit of crime reduction inevitably

causes harm that could be avoided. And, whether or not we like it

or accept it, we are responsible for the outcomes of our decisions.  return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q: Are you

trying to replace probation officers?

A: No. This technology is designed

to be available to probation officers, correction counselors, pretrial

release workers, and all others in the correctional system who make decisions

for offenders in the system. Judges continue to exercise major control

at the beginning of the correctional phase of a sentence - whether to imprison

or to supervise in the community is a decision which in most cases is up

to the judge to make. And it is the judge who weighs the safety risks which

militate for and against incapacitation or community supervision, as well

as the additional components of sentencing. Sentencing support technology

does nothing to shift the distribution of correctional responsibility between

judicial and correctional officers, but offers both enormously improved

information which they need to do their jobs more effectively.

An extremely positive recent development is

that the Multnomah County probation department (Department of Community

Justice) and the judges who regularly handle criminal cases have embarked

on a project to transform the role of the probation officer in probation

violation reports and hearings. Instead of coming to court looking

for vindication or disappointment in the threat of punishment to motivate

a probationer, probation officers would become the advocate for "what works"

in the courtroom, writing reports and arguing for outcomes based on expertise

about existing alternatives and sanctions, the offender in question, and

the literature of what works. Sentencing support tools are expected

to be part of this effort [probation officers who write presentence reports

are being trained on the tools first].  return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q: Is this all an argument

not to use jail or prison?

A: No. As I note elsewhere, we

have pretty good information that jail and prison (at least without unusually

good programming) do not generally reduce recidivism (and may even increase

it) after an offender is released, and the opponents of incarceration

often cite the literature to argue that community based treatment is almost

always the best disposition. But the only fair comparison is the

impact in terms of crime reduction from the time the sentence is imposed,

including

any period of incapacitation. After all, incapacitation is generally

the most effective thing we can do to reduce crime in the short run --

or as long as the incapacitation continues. The trick is to compare

(legally available) dispositions with and without jail or prison side by

side and examine which serves crime reduction best in the long run. Our

tools show that for some cohorts short or no incapacitation correlates

more highly with crime reduction, and for others longer jail or prison

sentences correlate more highly with crime reduction. For those who

fear that this approach inherently favors jail or prison, rest assured

that for most minor offenders, it does not -- even though jail or prison

presumably prevents recidivism while the offender is inside. Again,

to be responsible about public safety, we must insist at least that we

know what has worked best in the past without some bias for or against

jail or community based dispositions.  return

to top return

to top

Q: Aren't

you shifting responsibility from criminals to the courts when you blame

the courts (or criminal justice) for recidivism?

A: Emphasizing the responsibility

of courts (or of criminal justice) is necessary because for so long we

have avoided taking responsibility for the public safety outcomes of sentencing

on the theory that because criminals are to blame for committing crime,

we can't be blamed for not reducing it. Taking responsibility for doing

a better job with sentencing in no way diminishes the responsibility of

criminals. There are all sorts of reasons people commit crimes: bad character,

bad choices, bad luck, bad childhoods, bad values -- select any or all

that best capture "criminals" for you. My point is that we do various things

to people who are criminals with bad character, choices, luck -- etc. --

and that some of the things we do to some of them "work" better than some

of the things we do to others of them. To the extent that we don't make

our best effort to do to each that which is most likely to prevent the

next crime, we are responsible and (if it helps) worthy of blame -- and

it doesn't reduce, explain, or mitigate our responsibility (or blame) that

the offender is also to blame. In short, without making a responsible effort

to prevent future victimizations, we are not performing our public responsibilities

as we should -- and that reality in no way diminishes the responsibility

of criminals for their crimes; that criminals are responsible for their

crimes in no way diminishes our responsibility to do that which is most

likely to prevent crimes in the future at their hands. My point isn't that

we shouldn't blame criminals for crimes; it is that blaming them does not

excuse our failures to prevent future crime with our sentencing. Our legacy

is to celebrate their blame to avoid our responsibility -- and that's just

wrong.  return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q:

Are you saying retribution and general deterrence should be discarded as

objectives of sentencing?

A: What works to reduce crime is not the

only

purpose

of sentencing. But first and foremost, we should do a responsible

job of addressing which disposition (within those available) is most likely

to reduce criminal behavior. In assaultive or other dangerous crimes,

or even in compulsive property crimes, it may be that separation/incapacitation

is indeed the best result because we cannot sufficiently assure ourselves

or the public that non-incarcerative options will eliminate the risk. For

many minor crimes, at least with offenders with relatively few priors,

treatment, counseling, or other dispositions properly designed and delivered,

will be the best way to protect the public. Only after responsibly

addressing the crime reduction objective should we start going through

the other possible purposes of sentencing. When there are victims

whose recovery may depend upon the satisfaction of seeing punishment delivered,

and if the punishment necessary to accomplish their satisfaction is both

legally available and not disproportionate to the offense, it is certainly

appropriate to consider whether punishment is called for beyond (or even

instead of) what is most likely to work to reduce crime. In cases

in which what works is a close call, such a consideration may push the

balance in favor of a more punitive disposition than otherwise; in most

cases, what works will already satisfy all other present objectives of

punishment. In relatively extreme cases (such as a negligent homicide

perpetrated by an offender who needs little or no intervention to prevent

future crime, with victims' family members who have real needs for "justice"),

we may properly consider putting the needs of the victim ahead of the needs

of the community in overall crime reduction over the course of an offender's

potential career. And with some crimes, there are vulnerable victims

for whom punishment properly serves a therapeutic purpose -- such as sex

crimes against children who may feel responsible for the crime (but we

need to be careful here -- I try to get input from any treatment provider

to avoid compounding the victimization of a child who is suffering guilt

for causing the offender's punishment).

Some victims who come to court to be heard at sentencing

end up endorsing "preventing another victimization" as the highest priority,

though many are simply (and understandably) angry and hurt. It is

also worth noting that restitution, restorative justice, and compensatory

fines may be the best way to serve both the victim and the social need

for doing that which most likely prevents future criminal behavior by the

offender. But again, I don't deny that there are occasional (and

relatively rare) cases in which serving the victim's needs (or the needs

of the family of a deceased victim) may properly call for something more

punitive than that which is most likely to work.

Personally, I don't think the traditional interests

in what some western jurisdictions constructively call "denunciation" and

what we include within "retribution" -- or the largely preposterous argument

for general deterrence -- should ever justify doing something substantially

less likely to work when there is no specific victim (or victim's surviving

family) needing a punitive result. I understand that others will

disagree with me here. But this disagreement is trivial; my point

does not require consensus on this issue. My point comes down to

this:

We must stop enabling the notion that sentencing

is all about just deserts and "appropriate punishment" in the sense of

moral equivalency. To the extent that we have a ceremonial role (which

is presupposed, by the way, by the arguments for denunciation and general

deterrence), we judges must stop promoting what doesn't work by

ignoring what does. We should instead use our ceremonial leadership

and role to direct the sentencing process overwhelmingly toward what works,

but need not abandon the other purposes of punishment to be addressed in

the typical case with the same disposition, and in the rare case by rejecting

the result that would pertain if we only sought what works to reduce crime.  return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q:

How can you expect providers accurately to gather and report the data you

need?

A: We are not asking providers to gather

new information, and we are not relying on their information about their

effectiveness. DSS relies on existing (and growing) operational data. What's

new is not so much the information we collect but the ability to access

and compare the information we already have even though it is spread across

multiple databases. Providers used by the criminal justice system already

report failures; courts already keep track of pending and closed charges

and convictions, and record sentences and conditions imposed and probation

violation charges and results; law enforcement already records police contacts

and charges; and many of these and other databases record criminal histories

and offender characteristics. Because we can link offenders in these information

pools with data about what sanctions they have been subjected to (and failed

or completed) and what new charges and convictions and police contacts

they have generated after completion, we are already in a position to compare

programs' and sanctions' graduates performance for definable categories

of the population. As we gather more and more categories of information,

such as how offenders performed within jail, prison, or programs (in or

out of custody) we will continue to improve our ability to exploit this

information to make more accurate predictions about what is most likely

to reduce a given offender's risk to the community in both the immediate

and long-term future. But as soon as the technology is available,

existing data will enable us to make far more informed decisions than we

now make, and should help us do a far better job of diverting offenders

from criminal careers.  return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q:

What makes you think this technology will serve public safety?

A: Sentencing decisions are presently

made with virtually no information about how offenders behave after

being sanctioned, counseled, or treated by the various dispositions available

to us. Most sentencing decisions are based on whim, rumor, folklore, and

public relations, with a strong dose of myth. Although the better correctional

agencies do their best to study the research which is overflowing from

the shelves of academia, even they do not generally have access to actual

performance data concerning the programs and sanctions they have to chose

from. I submit that we cannot possibly be doing as well by accident as

we would with far better information about what seems to work best on which

offenders. Advantages are many: we can send offenders likely to benefit

from a program (in terms of reduced criminal behavior) to the right program

instead of clogging programs with offenders they can't affect; we can stop

using programs that don't work on anyone; we can make wiser decisions about

investing public dollars in correctional programs; we can do a better job

of using incapacitative solutions (typically jail and prison) on the offenders

who we can't expect to improve; and we can give programs information about

their performance so they can improve their product, their "client" selection,

and the basis of their competition with other programs for public dollars.  return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q: What

impact do you expect to have on recidivism?

A: In the foreseeable future,

we can expect that a substantial percentage of the correctional population

will continue in its criminal behavior interrupted only to the extent to

which we incapacitate offenders and they show signs of aging. Some other

substantial proportion of that population, however, is certainly susceptible

to more improvement than we now make by accident. Once we understand that

our approach to crime must transcend the focus on individual cases and

appreciate that we are managing criminal careers, we can recognize

that the attainable goal is to increase our success in diverting offenders

from those careers. With few exceptions, the vast majority of crimes are

committed by repeaters. Diverting an offender from a criminal career has

a multiplier effect on crime reduction; diverting an offender from crime

spares many people from future victimization and has long range economic

benefits as well. An analogy is health care - where we are learning that

wise management of early intervention has long-run benefits for the costs

of medical care throughout the patient's life. The health industry is rapidly

consuming DSS software for precisely this reason.  return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q: Don't we already know what works?

A: Yes and no. There's an enormous

volume of wisdom in research about what does and doesn't work. And

there is some common sense. In general, researchers tell us that

measured

by reduced subsequent criminal behavior, incarceration, scare

tactics, regimentation, and punishment ("scared straight," boot camps,

and the like) don't "work;" that "shock" probation and parole do not "work."

E.g.,

Oregon

Department of Corrections, "What

Doesn't Work to Change Behavior"; U.S.

Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of

Justice "Research in Brief" (July 1998).

What does work includes treatment programs that identify and address multiple

criminogenic factors with a methodology that is in fact (as opposed to

merely labeled) cognitive and behavioral. E.g., National

Mental Health Association, Treatment Works for Youth in the Criminal Justice

System; U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and

Delinquency Prevention Programs, Corrections

Rehabilitation and Treatment; Mark Gornik, Moving

from Correctional Program to Correctional Strategy: Using Proven Practices

to Change Criminal Behavior (U.S. Department of Justice, National

Institute of Corrections). Common sense may not be the best

guide on these matters, but it is persuasive (and not contradicted by literature)

on this point: offenders usually cannot commit crimes on the outside while

they are incarcerated. Literature seems persuasive on these refinements:

if the object of jail is to change behavior, short sentences, even for

repeated violations, work better than longer ones. And if the object

of incarceration is incapacitation, common sense is unrefuted: the longer

the offender is incarcerated, the longer the offender is incapacitated.

But if the offender is going to be released, the offender's inclination

to reoffend is as likely as not to be enhanced by long incarceration

unless incarceration includes effective treatment with community follow-up.

E.g,

The

Effects of Punishment on Recidivism, 7 Research Summary No. 3 (May

2002), Office of the Solicitor General of Canada, (citing Smith, P., Goggin,

C., & Gendreau, P. (2002) The effects of prison sentences and intermediate

sanctions on recidivism: General effects and individual differences

(User Report 2002-01) Ottawa: Solicitor General Canada). Another

settled principle: on many levels, it is overwhelmingly wiser to expend

correctional resources on "high risk" offenders than on "low risk" offenders,

with "risk" being measured by likelihood to recidivate (regardless of the

nature of the criminal conduct). Where among high risk offenders to focus

limited resources may reasonably depend on the nature of the risk: it makes

sense to give higher priority to preventing violent crimes than to preventing

property crimes.

There are a least three reasons why

knowing these things is not enough. First, we currently run sentencing

hearings as though we either don't know these things or don't want to know:

sentencing hearings are not about what works. A major reason for the sentencing

support tools is to help direct sentencing hearings (and all that precedes

and follows them) to the issue of how best to reduce recidivism.

Second, most of what we "know" is highly generalized. Most of the

studies are about what "works" on offenders in general instead of what

"works" on which offenders; they give us average outcomes. Some research

does indeed distinguish among risk levels and some focuses on specific

categories of crime; when the question is addressed, it is obvious that

some things work better on some offenders than on others -- an obvious

conclusion for educators who well know that different people learn differently.

Sentencing is and should be the occasion on which to apply what we know

in general to what we know about an offender, and to do our best to choose

(within applicable limits) that which is most likely to work on the particular

offender before us. Third, there is and has been a steady process

of research and learning within corrections for years. Yet when probation

officers come to court, they -- like everyone else -- rarely address what

"works." Even if the officer in question is committed to using best

practices, he or she may expect that judges don't welcome an analysis based

on what works -- presiding, as we do, in what gives all appearances of

a temple of just deserts. Our challenge is to support and encourage

best practices by the probation officers to whom we delegate so many decisions

about how to treat offenders, and to encourage them to give us their best

wisdom in the courtroom when we hear probation violations (or, in their

equivalent in some jurisdictions, conditional sentence violations) or read

their sentencing recommendations when we are fortunate enough to have a

presentence investigation report at sentencing.  return

to top of page return

to top of page

Q:

Why can't we just exploit the research we already have?

A: I'm not sure why, but I'm

sure we don't. At the 2002 international Sentencing

and Society Conference in Glasgow, Scotland, it was obvious that

disciplines having to do with assessing correctional program effectiveness

are entirely ignored by those that purport to study sentencing practices.

In brief, the response to popular anger at recidivism, conference participants

heard analyses of how "populist punitiveness" is improperly measured by

flawed polling practices, exploited by politicians, and inflamed by the

media -- but no presenter mentioned that there might be a basis for popular

dissatisfaction with our public safety performance. No input was

received or apparently expected from criminologists or corrections expects.

Participants received copies of the latest Annual Report of the British

Sentencing Advisory Panel, whose non-binding input is prerequisite to the

promulgation of sentencing guideline judgments by the Court of Appeal under

the Crime and Disorder Act of 1998. Incredibly, although the Act

expressly contemplates consideration of factors including "the cost of

different sentences and their relative effectiveness in preventing re-offending,"

the Panel apparently never considered using its resources to gather evidence

on which sentences might best prevent recidivism, and instead spent its

expert energy on public opinion polls. Those skeptical of this assessment

of the abyss between centers of sentencing "research" and centers of criminological

and correctional research are invited to read the abstracts

of papers presented at Glasgow; apart from the presentation reporting

on the project subject of this web site, only one paper suggested

that it might make sense to try to rationalize sentencing around a new

objective: public safety.

My experience at the 40th annual conference of the Academy

of Criminal Justice Sciences in March, 2003, reinforces my impression that